The Evolution of Super Senior CDS

Synthetic CDO’s

Starting at the beginning is a good place to start.

A synthetic CDO is a “CDO” made up of credit derivatives. A typical one would contain 100 “Reference Entities” or companies. They could be bigger, rarely were they smaller because that wasn’t optimal for the “tranching”.

The “first loss tranche” or “equity” tranche was in theory the one with the most risk. Depending on how the cashflow waterfalls were done, this first loss was actually the safest and had by far the best risk/reward, but that is a story we have written about in Free Equity.

Then there would be a “mezz” tranche. This would often be some combination of BBB through AA in terms of rating and was often the hardest to place. Again, depending on the waterfall, there were many deals that under no circumstance could the BBB tranche have a better return than the first loss tranche below it, but that was a flaw that worked to great advantage of many.

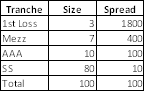

Then there was a AAA tranche. I will use some really really rough number, just so you have a handle on things. Let’s pretend that the first loss tranche was about 3% of the deal size. Then let’s say the Mezz tranches were about 7%, then that leaves 90% of the deal as AAA.

But 90% AAA wasn’t cheap enough. Why would you pay anything for the 100th default? Or even the 50th? With only 100 investment grade companies, even the doomiest gloomer can’t come up with a scenario of that many defaults – other than the nuclear option, at which point, who cares?

So better than AAA, or AAA+, or quadruple A was created, later to be affectionately known as super senior.

Rather than trying to buy a protection on a AAA tranche that is 90% of the deal size, banks started buying only a 10% AAA tranche. Pricing here had to be competitive with other AAA assets.

The banks were now left with the “nuclear” piece. They had protection on 20% of the deal (we can ignore that the banks often kept the first loss, since it was the safest part of the deal).

At a 0% recovery that means that 20 out of 100 investment grade companies could experience Credit Events during the course of the deal. That would be an unprecedented amount. If you assumed 40% recovery (which seems inexplicable with that level of default activity) the Super Senior Tranche could withstand 33 defaults before having any losses. There really was no way to conceivably get that level of corporate defaults and still care (ie, the nuclear option was required). That logic didn’t apply to sub-prime and CDO squared, but that is another story.

New Entrants Required

While in theory this super senior was super safe, it didn’t look good if the banks kept it. It was hard to get good regulatory capital treatment. It looked bad optically to have so much residual risk on the books. But who would sell?

Real money clients wouldn’t take the risk because they needed yield and would rather have AAA. They couldn’t afford to invest in such a tight spread product. Someone new had to come into the market. Someone not traditionally a big part of the market had to come in, but how to entice them?

Let’s go back to our simplistic, hypothetical example.

Let’s say the names trade on average at 100 bps (the CDS spread is 1% per annum).

You could pay 0.1% per annum and the “first lost tranche” would have a potential annual total return of 18% in a no default environment. I have simplified tranche size and cost, but the idea is about right.

So who would sell that much risk for that price? Who was in the business of taking tail risk? Who could look at this actuarially and get comfortable taking that risk? Insurance companies and monoline wrappers were well suited for this business. Or so they thought.

Anyways, FSA, and Figic, and Chubb, and others entered into this market. It was almost “free” money. I remember once the final 0.0025% of a negotiation was handled based on closest to pin.

So these entities would sell credit protection on $800 million at a time and receive 0.1% per annum (rough numbers).

Enron, Worldcom, and Collateral

Then Enron and Worldcom happened. September 11th happened. The internet bubble burst. All of a sudden there were a lot of investment grade companies in trouble. Although most people focus on 2008, we had a serious credit crisis back in 2001 and 2002.

The problem for the super senior was mark to market and collateral calls.

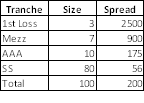

Let’s say that the average spread went to 200 bps from 100 bps. This alone would be a serious problem for the valuation of the “tranches”. In the above methodology, this 200 bps now needs to be spread across the tranches.

Now the super senior would be at 56 bps not the 10 bps. Again this is very rough, and how the pricing is spread throughout the tranches is very complex (it involves correlation, but also is impacted by the distribution of credit spreads of the single names, etc.). But the conclusion is the same, even with still low risk of ever having actual losses the market value can change quickly.

If the deal still had about 4 years left to maturity, the “duration” of the super senior would say have been about 3.5 (a measure of how sensitive the valuation is to a move in spread).

So in this hypothetical example the spread moved 46 bps, so a 1.6% total mark to market loss. Not bad and probably likely to never be realized.

The problem is the margin call. The client would be asked to post margin on this. On an $800 million trade, that would be almost $13 million of margin. Remember they are only earning $800,000 per annum. That wouldn’t be so bad, but the type of company that lives on selling tail risk tends to be highly leveraged. Tail risk protection selling tends to attract sellers who don’t have easy access to capital. They don’t issue a lot of bonds, they don’t have big lending arrangements. They earn tiny bits of premium income and hope never to pay off.

This margin call was a big deal and changed the market going forward.

Enter the Next Wave (can you say AIG)

Markets calmed down, spreads went tighter and everything was fine, but the market for super senior protection had changed for good.

The original writers weren’t willing to do it under terms that forced them to post variation margin. It was hard for even the most aggressive Wall Street desk to pretend these guys would be money good if called on without variation margin. Some deals got done, but a new breed of seller was necessary.

Welcome to AIG FP. Here was an entity that dealers could at least swear they believed would be able to pay. AIG FP was smart enough to know they didn’t want to post variation margin, but with a guarantee from AIG, dealers could at least get comfortable that they would be able to pay for losses.

Until this point the sellers of super senior had not been the big real companies of the world. Not that AIG FP itself was a big real company, but they were allowed to use the AIG guarantee, so dealers didn’t care about AIG FP and only looked to AIG.

Even here, some dealers, Goldman was probably the first, demanded “ratings” triggers. They would demand variation margin, but only if AIG was downgrade to BBB or something. That rating was so “unimaginably” low that AIG would concede. What no one (or at least very few people) thought of was whether AIG FP would get so big, that its positions would trigger the downgrades that would lead to margin payouts which would lead to potential default.

So the AIG “solution” was workable. Find some big entities that were real that were willing to post collateral only under what seemed like unlikely circumstances. Both sides could accept the deal. Wall Street never thought they would call on the actual protection, and now they had a strong counterparty, and would get collateral if the counterparty got weaker.

But how many AIG’s are there? How many firms could do this? How many would do this?

So there was a limit to how much protection could be bought from an AIG and the line to get that protection was deep – often with different groups within the same firm competing for AIG business.

And Leveraged Super Senior was Born

Leveraged Super Senior or LSS was then created. The dealers needed to offset more risk, but were running out of willing sellers. These weren’t necessarily bad trades and even the legendary Pimco total return fund has sold senior protection (though more at the height of the crisis than in normal times).

So investors were keen, but a new form to sell it in had to be created.

Again, back to the starting point that these are “nuclear” and no one really wants or needs the protection for economic reasons, it was far more about cosmetics and being able to get the accountants to sign off and booking full fees up front.

So if AAA is trading at a spread of 75 bps, how can you turn something that is only paying 10 bps, into something attractive?

Well, if I lever it up 20 times, and pay 150 bps, everyone is happy.

This is going to take some explaining, but it is actually elegant.

Let’s say you have a client [insert Canadian account here] who wants to make $800,000 but doesn’t want to risk $800 million to do it. What could you do? In a traditional deal the counterparty is on the hook for “full recourse”. The bank that buys protection is covered for up to the full amount. But seriously, who thinks there will ever be a loss on this portfolio? No one. How bad can the mark to market get?

That is the next angle. Let’s look at “non-recourse” deals. Let’s say this client has $40 million. So a deal is structured where the client gets exposure to $800 million, but only has a maximum loss of $40 million. In theory the spread would be 200 bps, but there are fees to be taken out, including the fact that the dealer retains a super super senior.

The reality is that the dealer has bought something different now. It has bought $800 million of protection, but can only ever collect $40 million. That is the “leveraged super senior”.

Since the bank isn’t into charity, the bank will typically strike it so that once the $40 million is used up, the deal is terminated. In fact, to give itself some “wiggle” room, the bank will have the right to terminate the deal at losses of say $38 million (leaving itself $2 million for unwind costs).

To get a $40 million loss on Super Senior, how much would the spreads need to widen? (I am going to stick to 5 year, but by this point in our history, credit spreads were so tight, many of the deals were 10 years, but let’s stick to 5 years).

Assuming a duration of 3.5, you would need a spread widening on the super senior of about 140 bps to get a 5% move to “knock out” the trade.

That seemed like a huge move at the time. In fact the IG7 index around the time this was popular (along with CPDO) was below 30 bps. People just didn’t think spreads could move that wide on super senior.

They did.

Managing the Recourse Risk

This is now the story of DB or at least how I guess it might have been.

They had bought LSS from clients. The leverage was large, but no one thought super senior could ever get so wide that you were near the trigger levels. When the deals were done, the trigger was so remote no one thought about what it would be like to trade super senior in a horrible credit environment.

When super senior was trading at 7 & 7 (7 bps per annum with only 7% subordination) you could trade billions in a 1 bp range. By the time super senior is trading at 50, that is no longer the case. Time and again, structurers, and the rating agencies, forget that liquidity is a function of spread, and of ratings migration.

The other issue, is how many people thought the business would be this big? If you had one deal near the trigger, then sure, time to sell isn’t horrible.

The problem was every desk had billions to go if the triggers were hit and the first one to trigger would likely move the market low enough to trigger the next worse deal and so on, cascading down the line. CPDO unwinds weren’t helping the situation.

So here is where the dealers were “stuck”. They had a trigger to exit with what they thought would be enough room. The realization was that it wasn’t going to be close. The death spiral risk was real, and probably not well modeled in.

So what happened next and what is this dark hole that allegedly occurred?

Market Disruption, More than an Excuse

It has been a long time since these conversations occurred, and I was only at the fringe, but I believe market disruption may have been a defined term, and an important one at that.

Under a “market disruption” it may have been possible to turn non recourse into recourse.

So without reading the documents, and yes it ALWAYS comes down to the documents in derivatives, it isn’t clear what rights people may have thought they would have been entitled to. That is real. It is unclear what assumptions they used. Did they model a 2 bp gap if they triggered? Are the whistleblowers saying they needed a 100 bp gap modeled?

At this stage it is very unclear. These positions should have been marked to market, so the issue is real, but it is far from clear whether they were mismarked or not without having the deal documentation.

The fact that we can be arguing about $12 billion in the financial system based totally on models and various accounting rules is beyond bizarre and enters the realm of the scary.

Disclaimer: The content provided is property of TF Market Advisors LLC and any views or opinions expressed herein are those solely of TF Market Advisors. This information is for educational and/or entertainment purposes only, so use this information at your own risk. TF Market Advisors is not a broker-dealer, legal advisor, tax advisor, accounting advisor or investment advisor of any kind, and does not recommend or advise on the suitability of any trade or investment, nor provide legal, tax or any other investment advice.